“Would it not be easier for the government to dissolve the people and elect another?” Thus asked the German playwright Bertolt Brecht (1898 - 1956) in one of his more noted poems. Called The Solution (Die Lösung), it contains Brecht’s take on the uprising that occurred over the course of two days in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in June 1953. Albeit famous, Brecht’s poem has never seemed more apt than now, with the right-wing AfD being excluded from power despite having gained the second-most votes (20.8%) in the recent general election. Should the new governing coalition — made up of Christian and Social Democrats and headed by Friedrich Merz — dissolve the electorate and elect another?

But let’s not begin with Brecht. Let’s begin with a politician who is nearly as famous as the Augsburg-born artist, and who, in terms of his Weltanschauung, can be seen as his soulmate. Let’s begin with Willy Brandt, who as a nineteen-year-old radical socialist had risked his life resisting the Nazis, and who spent the period from 1933 to 1945 in Norway, where he worked as a journalist and underwent a conversion from left-wing Marxist to Social Democrat. Originally from Lübeck, in the 1960s and 1970s Brandt emerged as the towering figure within Germany’s social-democratic movement. His finest moment came on 7 December 1970, during a state visit to Poland. In a powerful symbolic gesture that surprised everyone (including his own people and his Polish hosts), Brandt fell to his knees at the memorial to the Warsaw Ghetto.

“Mehr Demokratie wagen”

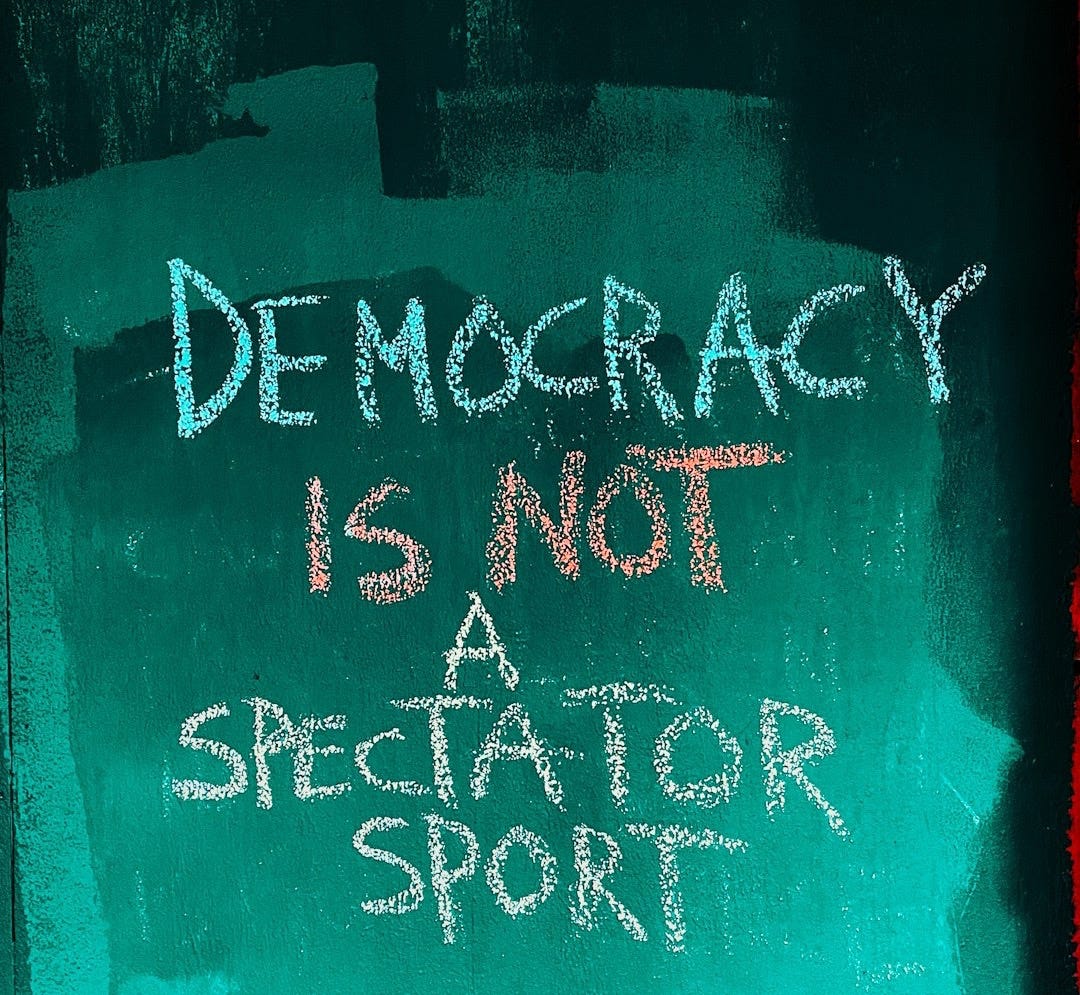

A good year before his historic visit to Poland, Brandt had been elected head of government, leading a coalition with the liberal FDP. On October 28, 1969, as the new German Chancellor, he called on the members of the Bundestag to allow more democracy in Germany in the future. “We want to dare more democracy.” This was the short sentence that turned a rather technical address by a new government into one of the most famous political speeches of the German post-war era.

Brandt delivered his speech at a time marked by economic prosperity and political fermentation. Germany had been politicised in the 1960s, mainly (but not exclusively) from the left. After the Marshall Plan and Erhardt’s social liberalism had enabled the German Wirtschaftswunder, which massively improved living standards in western Germany, the radical student movement put a whole series of demands to the new-old establishment. Aside from the denazification of institutions at all levels, it demanded that Germany (along with the rest of humanity) be rescued from capitalism and turned into a socialist model democracy. As one might expect, many of the leading proponents of that radical vision hailed from well-off families; people who had no trouble subsidising youngsters who chose to study Sociology, Philosophy, or History.

Brandt responded to these lofty demands with a measured proposal of reform. Expressing pride in Germany’s democratic accomplishments, he argued that German democracy could only be sustained through increased participation. The double self-criticism at the end of his speech — directed at both politicians and the electorate — fits in with this assessment: “The government can only work successfully in a democracy if it is supported by the democratic commitment of the citizens. We have as little need for blind consent, just as our people have no need whatsoever to be patronised from on high.”

A good twenty years after the collapse of National Socialism, the leader of Germany’s Social Democrats understood “daring more democracy” to mean that democratic self-responsibility was more important than the control of society by the state and its exponents in politics, public administration and business. Brandt justified the proposal to lower the voting age from 21 to 18 and the passive voting age from 25 to 21 with the prospect of gaining freedom: “We want a society that offers more freedom and demands more shared responsibility.”

To this day, most German politicians and intellectuals tend to be at a loss for words when asked to comment on Brandt’s famous speech. Many react with barely concealed embarrassment at the suggestion that something might be amiss with their democratic system, which they regard as a model for the rest of the world. They are especially proud of their constitution, the Grundgesetz, that armour made of natural law and extensive powers of judicial review. Most historians and political scientists, when asked about Brandt’s 1969 speech, argue that the great social democrat merely showed his commitment to the representative democracy enshrined in the German constitution. What it does not represent, they insist, is a call for some sort of direct democracy.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to HISTORYONICS to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.